I Was At Woodstock 99: Here’s How Accurate Netflix’s Documentary Is

As the second Woodstock documentary to come out in less than a year, Netflix’s Trainwreck: Woodstock ’99 is the most accurate one yet, and I should know–I was there. I was 18 years old, and about to head home for summer break after my first year of college. I was excited to see my high school friends again, and even more excited that a few of us had decided to go to Woodstock ’99 later that summer. Little did I know it would be one of the craziest experiences of my life, the Fyre Festival before Fyre Festival even existed.

Tickets were pricey–$150 dollars, the equivalent of almost $270 today. It was a huge chunk of change for a broke college student to hand over, but it was Woodstock ’99. It was going to be historic. We knew we had to go. The hefty ticket price should have been a warning about what was to come at the actual festival, a foreshadowing. But we were young, we were energetic, and there was no way we were going to miss that lineup.

To say Woodstock ’99 was a transformative experience was an understatement. My friends and I were all good kids, a little naive for having grown up in a small, rural town–we didn’t even drink–but we were music junkies and we’d been to dozens of concerts and music festivals already. We thought we were prepared. We were not. Nor, it seemed, were the Woodstock ’99 festival organizers. Here’s what Netflix’s Trainwreck: Woodstock ’99 got absolutely right about the festival–and what details it missed.

Having It At An Air Force Base Was A Terrible Idea

Festival organizers had hyped up Woodstock ’99 as the event of the decade, and as a result, hundreds of thousands of tickets had been purchased. Organizers needed to find a place that was huge, relatively cheap, and not in use. They settled on Griffiss Air Force Base in Rome, NY, a defunct military base that had shut down in 1995. It was 3,689 acres of land sitting there unused, with airplane hangars already ready to go–perfect for raves and other events. At the time, it briefly crossed my mind that it was ironically funny that this festival being hyped up as a «countercultural revolution» was being held at a site symbolic of our military-industrial complex. But what it symbolized turned out to be the least of the location’s problems.

Here’s the problem with a military base: it’s almost all tarmac. Black asphalt that traps heat and turns everything on the ground into a scorching bed of what feels like actual lava. It might not have been so bad in the shade, except there was no shade. Military bases aren’t exactly known for their aesthetics and ecologically-friendly design. There were no trees to cool people down, no shade anywhere, no breeze. There was nothing but giant hangars being used for various events, the stages, the vendor and medical tents, and our own personal tents, which felt like sleeping in a stuffy oven. Already, the location had set Woodstock ’99 up for, if not failure, then certainly more problems. But it got worse.

There Were Way Too Many People

When Woodstock ’99 began, it had been estimated that about 250,000 people would attend over the weekend based on the number of ticket sales–a quarter of a million people. It was more people than I had ever seen in one place in my life. Except the actual number of people ended up being closer to 400,000. Piping, plywood, and chain link fences don’t keep people out when they’re determined to get in and your «security» force is both woefully understaffed and undertrained.

I remember hearing rumors start to circulate the first night that there were people without tickets sneaking over the fence. Being a «good girl,» I was a little in awe of their daring and secretly supportive of their sticking to–someone. I didn’t know who, but they were circumventing adults, and adults meant control. As it would turn out, however, adding an unexpected 150,000 people to Woodstock ’99 caused a terrible chain reaction. More people meant way more tents. Way more tents meant people who had planned to pitch their tent in the designated camping area, which was grassy, now had to pitch their tents right on the tarmac. You could barely navigate through the tents; they were right on top of each other, tent strings and lines crisscrossing everywhere. If you didn’t have the memory for direction like a homing pigeon (luckily, I and another friend did), you could wander for an hour in the campground before finding your tent. That many uninvited caused other problems, too, as we’d soon learn.

The Mud People Were To Be Avoided At All Costs

Aside from the fires, some of the most iconic images from Woodstock ’99 are the hordes of mud-covered people who roamed the grounds between the vendor section and the main stage. We quickly learned to avoid them. They weren’t a problem on the first night. The first night of Woodstock ’99 was great. It hadn’t yet grown scorching, the place hadn’t yet been trashed. My friends and I sat on a hillside just off the main stage, and it was calm–almost serene, even, as a light, humid breeze blew over us. There was already some littering on the ground, though, and the grass was quickly being trampled. I remember thinking I’d never seen so many drugs in my life; I saw at least different five kinds of drugs being passed around by the people near us. Just like with the fence-jumpers, I was a little shocked and a little thrilled that these people were bold enough to not only do drugs, but to do them right out in the open. Still, that first night was pretty peaceful and despite the bits of litter already blowing around, the place was intact.

That quickly changed the next day when Woodstock ’99 birthed a new species of horrible creature: the Mud People. On that Saturday, my friends and I spent the first part of the day wandering around and exploring the place, and in the afternoon, we headed toward the main stage to get a good spot for the big acts that night. When we arrived at the transitional area from the vendor and food section to the giant field before the main stage, we were greeted with the sight of hundreds of people covered in mud splashing around in what had become a squelchy, sticky bog of mud in the center of the field. My one friend thought it looked like fun and started to walk toward them, intent on joining in on the mud fight.

«Wait,» I said, grabbing his arm. «I don’t think you want to do that.»

«Why not?» he asked.

I pointed to the right, where there was a huge beer garden. «It’s scorching, it hasn’t rained in ages, and I don’t see any of them drinking beer or holding empty cups.» Then I pointed up at the Port-o-Pottys up on the hillside to the left of the bog, half of which were already overflowing with human waste and tipped over. «Where do you think that mud came from?«

We gave the Mud People a wide berth every time we saw them after that.

The Attendees Were Treated Like Cattle With Bank Accounts

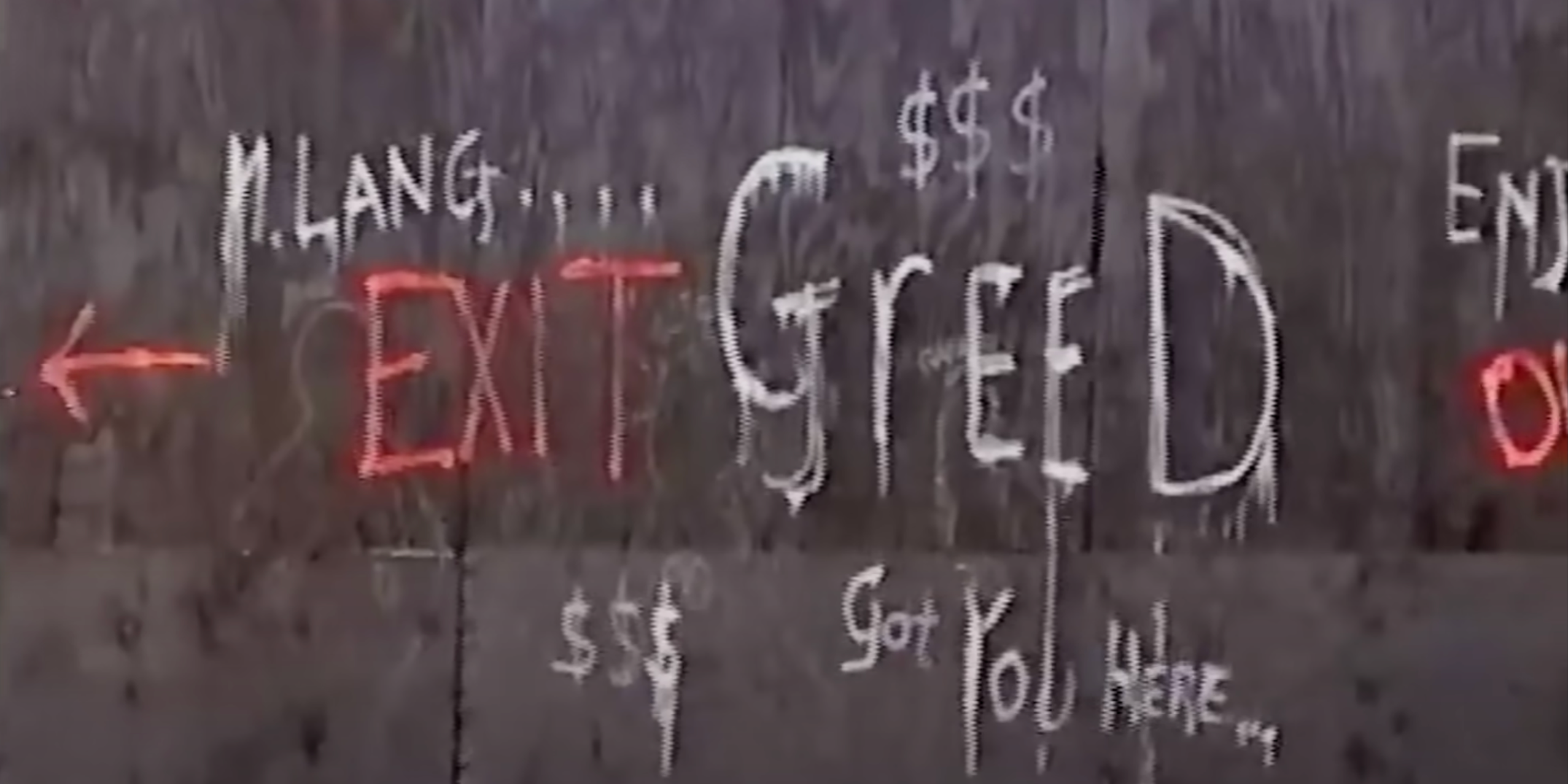

Shelling out $150 for a ticket was painful, but worth it if one considered it was really more like $50/day for a history-making event. Naively, I assumed that the expensive nature of the ticket meant that prices could be kept down at the actual event. The opposite was the case. The first Woodstock in 1969 had free food, open kitchens for all. As Trainwreck: Woodstock ’99 showed, the version held 30 years later was an appalling display of capitalism and corporate greed. Nothing came for free save for cheap promotional souvenirs that simply became another thing to carry. The vital stuff – food and water – came with a hefty price tag.

The cost of a bottle of water was the biggest source of sticker shock, and, later, the biggest source of anger. Water was selling for $4 a bottle on the first day, and as the temperature soared and the dehydration grew, the vendors, who were completely unregulated, started charging even more. While a little pricey, $4 for a bottle of water doesn’t sound too bad in 2022–but this was 1999. It would be the equivalent of paying $30 for a bottle of Aquafina now, and food was even more expensive. The cost of everything was staggering, the price gouging completely out of control, and very few Woodstock ’99 attendees had prepared for it. We were getting our first taste of a completely unregulated capitalist micro-market, and it was enraging. I’m generally a calm, polite person, but at one point I held up a $10 bottle ($18 in today’s terms) of cheap, off-brand water and asked the vendor, «Are you kidding me? It’s 100 degrees.» I meant that literally. Temperatures had soared to 100°F and it was almost 120 on the tarmac and in the mosh pits. The oppressive humidity made it even worse. He merely shrugged.

The Showers Were Horrifying

One thing Trainwreck: Woodstock ’99 glossed over was the terrible condition of the showers–if you could even call them that. The shower area was a huge, makeshift stall hastily constructed with plywood: one side for the guys, one side for the girls. The «showers» consisted of long pipes with holes in them every few feet, out of which would come a tired trickle of lukewarm water. Fully washing the shampoo and conditioner out of your hair was virtually impossible. There were no stalls; everyone showered together in one open area that was quickly flooded with a few inches of filthy water swirling around. Worse, with it being constructed of mere plywood, with a huge gap between the ground and plywood between the two sides, there was nothing to stop guys from peeking under to the girls’ side–or even climbing under. And quite a few did. I decided the first shower I took was my last when I looked down and saw a guy’s leering face just two feet away. It just wasn’t worth waiting in line for an hour only to stand in dirty slop water, even with flip-flops, and be ogled by perverts who thought being at Woodstock ’99 gave them carte blanche to sexually harass or abuse women. It’s easy to see why they did–there was certainly no security that stopped them. Eventually, people started bathing in the portable fountains–and ended up getting trench mouth from the amount of feces that had contaminated the water.

The «Security» Guards Were Literally Just Kids Like Us

As for that security–which Woodstock ’99 organizers had optimistically named the «Peace Patrol»–it was as much of a disaster as the rest of the festival. It’s not that there weren’t actual trained security forces there–there were–but they had their hands full trying to keep people in the mosh pit mostly alive and the talent from being assaulted by flying debris. Plus, the percentage of trained professionals on the Peace Patrol was small compared to the number of schmucks organizers had simply pulled off the street to be a cheap security force. Quite a few of them appeared to be around our age or a few years older, which confused me. I stopped a baby-faced, yellow-shirted security guard out of curiosity: «I was just wondering–how long have you been a security guard?» He laughed, «Oh, I’m not! They said they’d pay me $500 to be one of the Peace Patrol and I said, heck yeah.» I later learned there were Peace Patrol guards who had sold their yellow security t-shirts to random festival-goers who thought it would give them access to backstage areas or to harass women with impunity. It certainly explained why I saw so many of the «security» guards joining in on the very things they had been hired to stop. That included quite a few yellow-clad men in the crowds of guys that would surround a girl and chant at her to take her top off–or worse. They weren’t there to break up the crowd of threatening men; they were part of it.

In fact, the entire weekend of Woodstock ’99, I only saw one guy in the entire festival stick up for the women who were being rampantly sexually assaulted. That was Dexter Holland, frontman for The Offspring, who actually stopped in the middle of their set to call out how much groping he saw happening to the women surfing in the crowd in front of the stage, telling guys to knock it off. Of course, he somewhat bobbled the landing when he followed that up by yelling, «If you’re a girl and you see a guy go overhead, I want you to grab his f*****g balls!» But hey, it was 1999, and that’s about as progressive as it got when it came to the issue of consent. Dexter rocketed up my favorites list after that.

Fred Durst Refused To Stop His Set To Let Medical Evac People In The Pit

Woodstock ’99 can be marked in two ages: B.L.B. and A.L.B: before Limp Bizkit and after Limp Bizkit. Fred Durst and Limp Bizkit are the clear point at which Woodstock ’99 took a turn for the worse, but to lay the blame squarely at their feet would be to ignore all the other ways festival organizers had skinflinted Woodstock ’99 into disaster. It would also be ignoring the fact that organizers hired Limp Bizkit to do exactly what Limp Bizkit does. Still, Fred Durst didn’t exactly help paint himself in a good light. He had the entire frenzied crowd in the palm of his hands and might have chosen to calm them down. Instead, he took that vibe of angry energy running through the crowd and amped it up.

When it was clear that people were being tramped in the mosh pit, some being badly injured, I started hearing a murmur running through the crowd that medical personnel wanted Limp Bizkit to stop their set so security could pull the injured people out. Fred Durst refused. Shortly thereafter, either his mic or the bank of speakers near the stage stopped working for a few minutes. We were never positive, but the rumor flying around was that the festival staff had pulled the plug on purpose to give the crowd time to calm down since Fred Durst wouldn’t do it himself. I wouldn’t be surprised either way.

James Hetfield Tried To Calm Things Down But It Was Too Late

While Trainwreck: Woodstock ’99 certainly focuses on the crowd turning to violence during Limp Bizkit’s set, what it skipped are the bands that came after Limp Bizkit on Saturday night. After Limp Bizkit, Rage Against the Machine took the stage. While Rage and LB harnessed the same rage against injustice, it was different. Rage Against the Machine sang songs about the military-industrial complex and capitalism; Limp Bizkit sang songs about being angsty and girlfriends cheating. They were not the same. Unfortunately, the Woodstock crowd was far more in the mood for Fred Durst’s whiny, entitled form of violence than Zack de la Rocha’s intellectually focused activism.

By the time Metallica came out to close out Saturday night, lead singer James Hetfield was well aware of what Fred Durst had done and that there was a vicious, angry edge running through the crowd. You could feel it thrumming through the crowd, the jagged, spiky energy of an intense crowd with a lot of angry turmoil and nowhere to focus it. It was unsettling, and Hetfield and the rest of Metallica clearly felt it as clearly as my friends and I did. As a veteran of the stage and a consummate professional, James Hetfield did his best to redirect the energy of the crowd back at him rather than at each other, and to turn it from anger to enthusiasm. Not being drunk or out of my mind on drugs, as well as close to the stage, I could see Hetfield heroically doing everything he could to get the furious energy to recede. They played for almost a full extra hour at the end of an already incredible set, all in order to act as a release valve and bring down the temperature of the crowd. But it was too late. All that energy, once uncorked, could not be contained.

Later, after I got home, I learned that a guy named David DeRosia had collapsed during Metallica’s set and died two days later. His body temperature was 107°F at the time. I remember wondering if Metallica knew, and how they felt, seeing as how they had tried so hard to stop anything like that from happening.

It Was Like Escaping A War Zone

Trainwreck: Woodstock ’99 did a great job of capturing just how chaotic and dangerous the Sunday night riots were. However, most of it was told from the perspective of the staff, rather than the attendees themselves. For my friends and I, it started out as a distant threat. We were far up in the crowd, watching Red Hot Chili Peppers do their thing and laughing at the bassist, Flea, dancing around in nothing but a sock. When the announcement came that the set was pausing to let the firetrucks through, we were confused. Fire? What fire?

Being only 5′ tall, we decided to put me on the shoulders of my friend, who was 6’4″. I could finally see above the crowd, and when he turned around, I could see all the way to the back of the massive crowd. «Oh my God,» I said. «He wasn’t kidding. Everything is on fire!» The minute RHCP’s set ended, we booked it for our tent to grab our stuff and make an escape. At least, that was our intention. As it turns out, a quick getaway is impossible in a full-on riot.

When I say making it back to our tent that night was like running through a war zone, I mean it. Everywhere, I could see groups of angry young white guys tearing down the Peace Wall, tearing down vendor stands, tearing down tents, fighting, destroying everything they could get their hands on. The vendor stalls were locked up. The medical tents sat empty, most of the medical personnel having fled after realizing a large portion of the crowd could no longer tell friend from foe–and didn’t much care. At one point, I sprinted past a scene of pure idiotic anarchy: a guy on top of a sound tower full of speakers, waving his shirt around his head and screaming while a group of guys turned the bottom of it into a ring of fire. I was more than a little shocked that they were so lost in their primal, violent lizard brains that they never even realized they had turned it into a pyre, and the guy on top couldn’t get down now.

Fire was everywhere. Smoke was everywhere. And there were a few jarring booms as the propane tanks in supply trailers blew up. This wasn’t a few hundred kids acting out and being wild–this was something else. After days of being treated miserably and squeezed for every last penny, the closing night of Woodstock ’99 felt more like a generation rising up to destroy a system that had never worked for them or people like them and never would. And I got it. I didn’t condone it; I knew the Venn diagram overlap of the guys who had sexually harassed or assaulted women and the guys who were rioting was quite large. I was horrified at what was happening around me. I wasn’t a violent person and still am not. But even as young and naive as I was at the time, I recognized that the unbridled rage pouring from so many people wasn’t about Woodstock, not really, but about everything, an entire ideology that needed to burn to the ground.

My friends and I eventually made it back to our tent, then back to the car. We ended up driving through a hole that had been torn in the fence by angry rioters. I got home none the worse for wear than sunburned, dehydrated, and with a boot-shaped bruise on the side of my face. At the time, I said I’d do it again in a heartbeat. But watching Trainwreck: Woodstock ’99 and looking back on it made me realize it all ended in an experience I’d never want to repeat.